Orchestration of Sonorities in Renaissance Polyphony

Orchestration of Sonorities of Renaissance Polyphony

Amazing Moments in Timbre | Timbre and Orchestration Writings

by Ben Duinker

Musical composition in the European Renaissance developed into stylistically diverse, multi-part vocal polyphony, perhaps best known today through the work of 16th century composers such as Josquin, Victoria, Palestrina, Byrd, and Lassus. Much of our current analytical fascination with this repertoire is grounded in the topics of mode and counterpoint. These topics are usually understood linearly; we might think about how a single voice part within a composition expresses a mode (one of the prevailing systems governing the organization of pitch in this period), or how multiple voice parts move against one another (counterpoint, from the Latin contrapunctus—literally means note-against-note), creating successions of intervals. This essay focuses on the amazing moments ensconced in those intervals: the way they are arranged, the spaces between them, and ultimately, the sonorities they create.[1]

In this context, a sonority is created when two or more voices sound against one another at a non-unison interval. While polyphonic compositions date back centuries earlier than the high Renaissance, it was not the norm for composers of this era to notate vocal polyphony in score form (each voice part was notated individually in separate books for each part). Early examples of score-notated compositions only begin to appear—and not yet with regularity—in the later 16th century. Likewise, theoretical discussion of polyphonic sonorities also begins much later than their use in practice, perhaps most famously in Pietro Aaron’s Toscanello in Musica (1523). Indeed, Aaron’s eloquent table (Example 1) that determines appropriate placements of voices in four-part contrapuntal writing does not use score notation: based on the interval formed between soprano (usually called the superius or cantus) and tenor, one can determine what pitches are possible for the bass and alto voices.

Example 1: Excerpt from Toscanello in Musica (Aaron, 1523), demonstrating the author’s system for generating intervals between voice parts. The values in the leftmost column represent the tenor’s intervallic distance below the cantus. (Note that intervallic distances here are integers, meaning minor and major thirds are both III, for example.) The values in each bassus and altus column correspond to one another (i.e., the leftmost column of bassus corresponds to the leftmost column of altus). The bassus values represent intervallic distance below the tenor, while the altus values represent intervallic distance above the bassus, unless slashes accompany the number, in which case representing bass distance above the tenor and altus distance below the bassus.

Though unrelated, these two developments of the 16th century—compositional “scores” and theorization of sonorities—each lay important groundwork for understanding the rhetorical and affective power of sonorities in Renaissance polyphony. If orchestration involves the “skillful selection, combination, and juxtaposition of [sounds] … to achieve a particular goal,” then momentarily removing sonorities from their contrapuntal context can encourage us to think of them as orchestrational devices—their intervallic composition bears these affective or rhetorical qualities on its own.[2] Though the florid counterpoint created by Renaissance composers certainly demonstrates structural eloquence, it is difficult to imagine that Lassus was not, for example, “thinking vertically” when composing the striking opening of Miserere Mei Deus, a setting from his Seven Penitential Psalms of David (1584) (Example 2). As you listen, pay attention to how the harmonic motion of this passage seems to progress smoothly, almost effortlessly. There are many rich moments in Collegium Vocal Gent’s recording of this work where a particular vertical sonority is so stunning it stops the listener in their tracks. These are places where I almost wish Lassus had used longer rhythmic values so I could savour these sonorities more thoroughly.

Example 2 (audio): Opening of Miserere Mei Deus (Lassus, 1584), performed by Collegium Vocale Gent (dir. Philippe Herreweghe)

Renaissance polyphonic compositions—or sections thereof—typically conclude with sonorities held on relatively longer note values, and usually these sonorities include a combination of thirds, fifths, and octaves above the lowest sounding note. These features enable us to compare various final sonorities from the same composition, allowing us to question why some sonorities might sound more pleasing to us than others, or simply why sonorities sound the way they do. Example 3 compares the final sonorities built on the pitch-class A in three sections of the Agnus Dei from Jean Richafort’s Requiem (1521), documenting these as performed by the King’s Singers and comparing their orchestrations. While listening, think about how you would describe each sonority. What musical factors are giving rise to these descriptions?

One factor likely driving your perception of these sonorities is their voicing: the distribution of individual voices within the sonority. Voicing can be thought about in many ways: the number of unique voices in the sonority, the presence of all three members of [what we now call] the triad, its pitch span (the intervallic distance between lowest and highest sounding voices), pitch locus (how low or high the voices within the sonority tend to sit), spacing tightness (how closely spaced the voices are), and evenness (how evenly spaced the voices are). The intricacies of voicing are compounded by a variety of performance factors—how many singers are performing each part, the nature of the vowel sounds they produce, or the acoustics of the performance venue. Thus, while voicing goes some way in explaining orchestration in Renaissance polyphony, these other factors introduce variability from performance to performance, recording to recording.

As we can see in Example 3, each sonority has a different number of unique voices and sonority B lacks a third above the lowest sounding pitch. Total pitch spans are identical for sonorities A and C and only slightly smaller for B. Sonorities A and C are nearly identical. If we look closely, the only difference is in the tenor voice, which occupies the low fifth in sonority A and doubles the octave in sonority C. Sonority A’s spacing is thus both tighter and more even. Take another listen. If you—like me—felt that sonority A sounds the “fullest,” and sonorities B and C sound comparatively empty or hollow, this observation regarding the tenor voice in sonority A might explain why—sonority B is the most evenly spaced but lacks the chordal third and is less tightly spaced than sonority A. Sonority C, while possessing all members of the triad, includes an octave between adjacent voices, which means it is less tightly and evenly spaced than the others.

Example 3 (with audio): Final sonorities of each section of the Agnus Dei from Jean Richafort’s Requiem im Memoriam Josquin des Prez (1532), performed by the King’s Singers. Voicing of the three final sonorities excerpted in Example 4. Sonority B stands out for its lack of third above the lowest sounding note, and sonority C lacks the lowest fifth (in the Tenor) found in sonorities A and B.

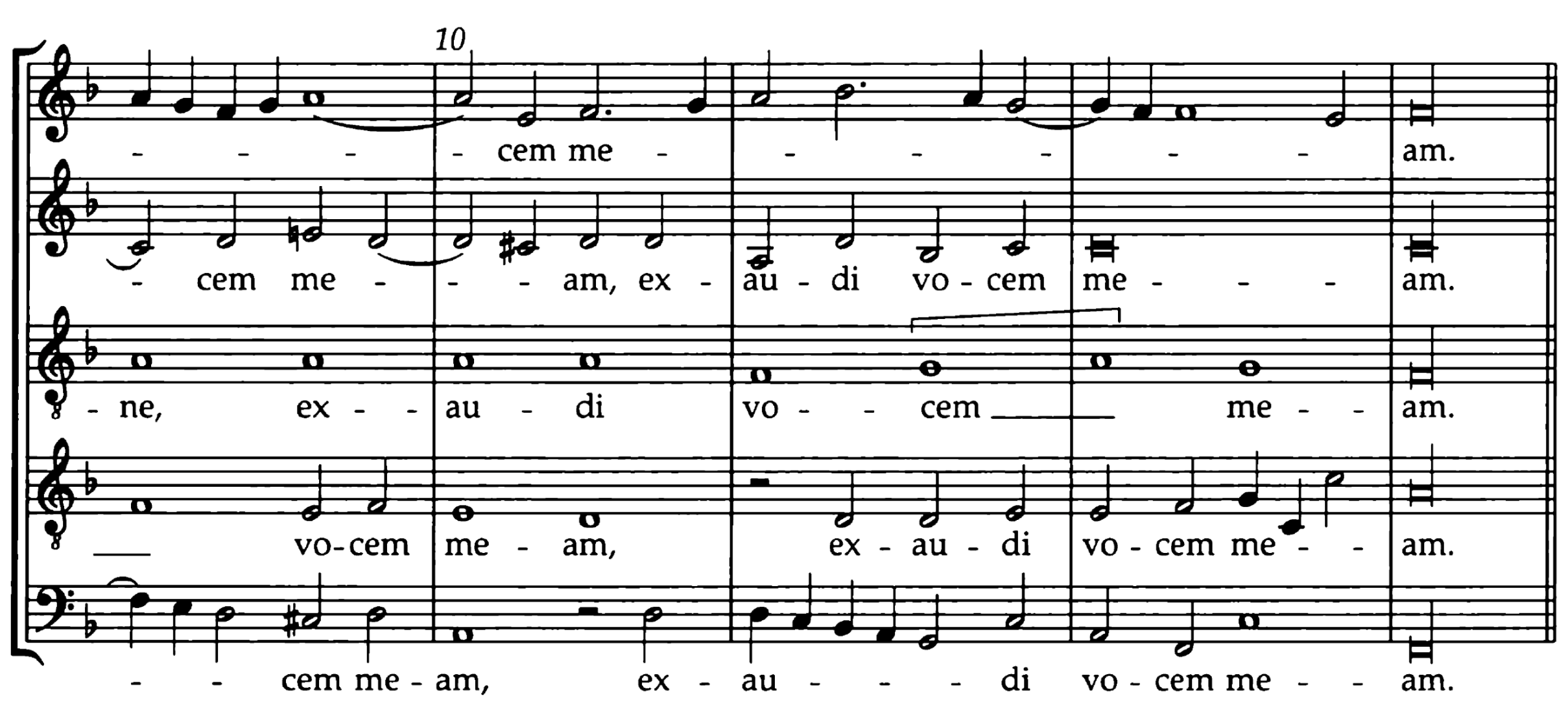

We cannot positively determine why Richafort chose to voice sonorities A and C differently. The differences arise in freely composed voices—not from a voice that was borrowed from another composition, which was a common compositional tool at the time. But in other cases, composers might have a very practical reason to choose a specific voicing in a final sonority. Let’s return to Lassus, this time De Profundis Clamavi, the sixth of his Seven Penitential Psalms of David (1584). Like Richafort’s Requiem, this composition uses a cantus firmus: a fixed, pre-existing melody derived from medieval plainchant. In Example 4a, we can see the cantus firmus in the tenor (middle) voice, easily identifiable due to its consistently long rhythmic values. Lassus’s cadence at the end of this section uses the common outward sixth-to-octave expansion in the discant and tenor voices, and the remaining three voices fill out the final sonority, giving us the final voicing. Contrast this with a later section of the work (Example 4b), where the cantus firmus, now in a lower register, is set in the Quintus voice. It ends this section on C, but the parts collectively again cadence to F, as shown. This cadential gesture is quite like the first one—note the similarities in the outer voices—but now since the cantus firmus is lower, the final sonority is voiced differently. Listen to these passages side by side, focusing on the differences between their respective final sonorities. Though Lassus voiced these in accordance with his cantus firmus (which he inherited from a previous composition and did not alter, as was custom), they nevertheless sound quite different from one another. Which do you prefer? How would you describe the comparison between them?

Example 4a (with audio): De Profundis Clamavi (Lassus, 1584), end of first section. Note the cantus firmus in the middle voice, ending on an F that forms the midpoint of the final sonority.

Example 4b (with audio): De Profundis Clamavi, end of sixth section. Note the cantus firmus in the second-to-lowest voice, ending on a low C that forms a low fifth in the final sonority.

Perhaps your response to these questions revolved around the presence or absence of the lowest fifth in the sonority. In Example 4a there is no “low fifth” in the final sonority while in Example 4b there is, in the second-to-lowest voice. The mere presence of this low fifth will lower the pitch locus. This outcome is a product of Lassus’s pre-compositional decision to set the cantus firmus in a lower voice and in a lower register. In other cases, the decision to include a low fifth in the final sonority seems more deliberate. Consider the final moments of the hauntingly beautiful, seven-voice Agnus Dei in Cipriano de Rore’s Missa Pater Rerum Serium, his mass built on a motet of the same name attributed to Josquin des Prez. Rore reaches the final sonority with no low fifth, yet follows Josquin’s original motet, which adds one in the bass voice as a final gesture (highlighted in Example 5). The Bassus II, which begins this final sonority on G, has moved there to avoid parallel octaves with the Altus. Thus, Rore (and Josquin before him) has deliberately reassigned the Bassus II to the low fifth in the final chord. This compositional decision is not an outcome of anything to do with the movement’s contrapuntal structure. If so, why has it been added here? What effect does it have on you as you listen to the Huelgas Ensemble perform it? Does it make the sonority seem more “final”?

Rore is not the only composer to use this technique of adding a low fifth after the final sonority has been reached in all other voices. For example, Richafort’s Requiem (see above) does so in all its movements, and in his composition In Ecclesis (Symphoniae Sacrae Liber Secundus, 1615), Giovanni Gabrielli’s trombones triumphantly intone the low fifth after the work’s final sonority has been established. It is as if, the only thing more a composer can do, upon reaching a final sonority, is to thicken its texture with this “low fifth.” Whether composers of the time thought about it this way, the low fifth we are discussing here seems to have a marked effect on textural thickness—pulling the pitch locus downward and often creating a more even spacing of internal intervals—and thus serves as a potent orchestrational tool in renaissance polyphony. In so doing, it draws attention to the broader notion of textural thickness in this idiom.

Example 5 (with audio): Final measures of the Agnus Dei from Missa Pater Rerum Seriem (Cipriano de Rore, undated).

In their textural thickness, momentary pitch stasis, and myriad possible intervallic combinations, final sonorities—and sonorities more generally—are rhetorically powerful and aurally salient elements of 16th century Renaissance vocal polyphony. Renaissance composers had various orchestrational techniques available to them that could be harnessed to specific effect. For example, in its fullness, the “low fifth” can perhaps impart a sense of greater finality when it is added to a final sonority, as shown here in works by Lassus and Rore. Likewise, when comparing successive final sonorities in Richafort’s Agnus Dei, we see how subtle changes to the voicing can produce dramatically different sounding sonorities, each with their own characteristics. Theoretical and compositional advancements in the Renaissance bear remarkable independence from one another and the historical details of their manifestation remain, in many cases, not well understood. And while polyphony—and the sonorities that result from it—predates the high renaissance by several centuries, its zenith in the 16th century reveals a nuanced attention to sonority construction, especially in works with 5 or more voices, where the voicing options of each sonority becomes manifold. Indeed, the voicing of sonorities represents an amazing moment in the history of orchestration, and sonority/chord voicing as an orchestration tool has remained an important component of Western music since then.

Bibliography

Fuller, Sarah. 1986. “On Sonority in Fourteenth-Century Polyphony: Some Preliminary Reflections.” Journal of Music Theory 30: 35–70.

McAdams, Stephen, Meghan Goodchild, and Kit Soden. 2022. “A Taxonomy of Orchestral Grouping Effects Derived from Principles of Auditory Perception.” Music Theory Online 28 (3).