photo credit: www.gemmanew.com

Orchestrational narrative in Gustav Holst’s The Planets

Dialogues, with Gemma New

With Kit Soden and Jade Roth

27 September, 2023 | Published 6 June, 2024

Gemma New, Music Director of the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra and Artistic Advisor and Principal Conductor of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, joined us to discuss her interpretation of Gustav Holst's iconic work, "The Planets." As a sought-after conductor known for her insightful and dynamic performances, New shared her thoughts on the orchestrational narrative of the piece during her tenure as a guest conductor at the Orchestre symphonique de Montréal in 2023.

In this in-depth interview, New discusses the unique instrumental combinations and timbres that Holst employs to evoke the distinct characteristics of each movement. She delves into the challenges of balancing the various sections of the orchestra, crafting effective phrasing, and interpreting the composer's intentions to create a cohesive and compelling performance. Drawing upon her extensive experience conducting top orchestras worldwide and her commitment to showcasing contemporary works, New provides a fresh perspective on Holst's timeless masterpiece.

Kit Soden: As far as the programmatic aspect of The Planets, are there instrumental combinations that you find bring out certain characteristic elements?

Gemma New: Well, I did like that already in the questions you sent me. You assumed that the character has a lot to play with the choice of colour, and really that's exactly what this is about. Because Holst's chosen a personality, a lot of personality traits for each tone poem, and then made a sound world out of it. And so just the first bar [1], that colour combination, for example, if we want to make it specific, the timpani, just one at the moment, but there are two in the piece, which he is saving for later. But the gong gives an aura effect of maybe the dust coming out as an army marches. We have a little bit of that dust, and that's what the gong gives from their feet treading. We have col legno, which at a quiet part we use a little bit of the hair of the bow as well as the wood and it works really well. Jeté, very hard to get that triplet and the 8th notes, and often the challenge is that the quarter notes then rush or weaken, it depends on the orchestra really. But we have very good rhythm here for this concert with the OSM. We've worked on it and it's amazing. And then the two harps of course being very low down there creates our army already.

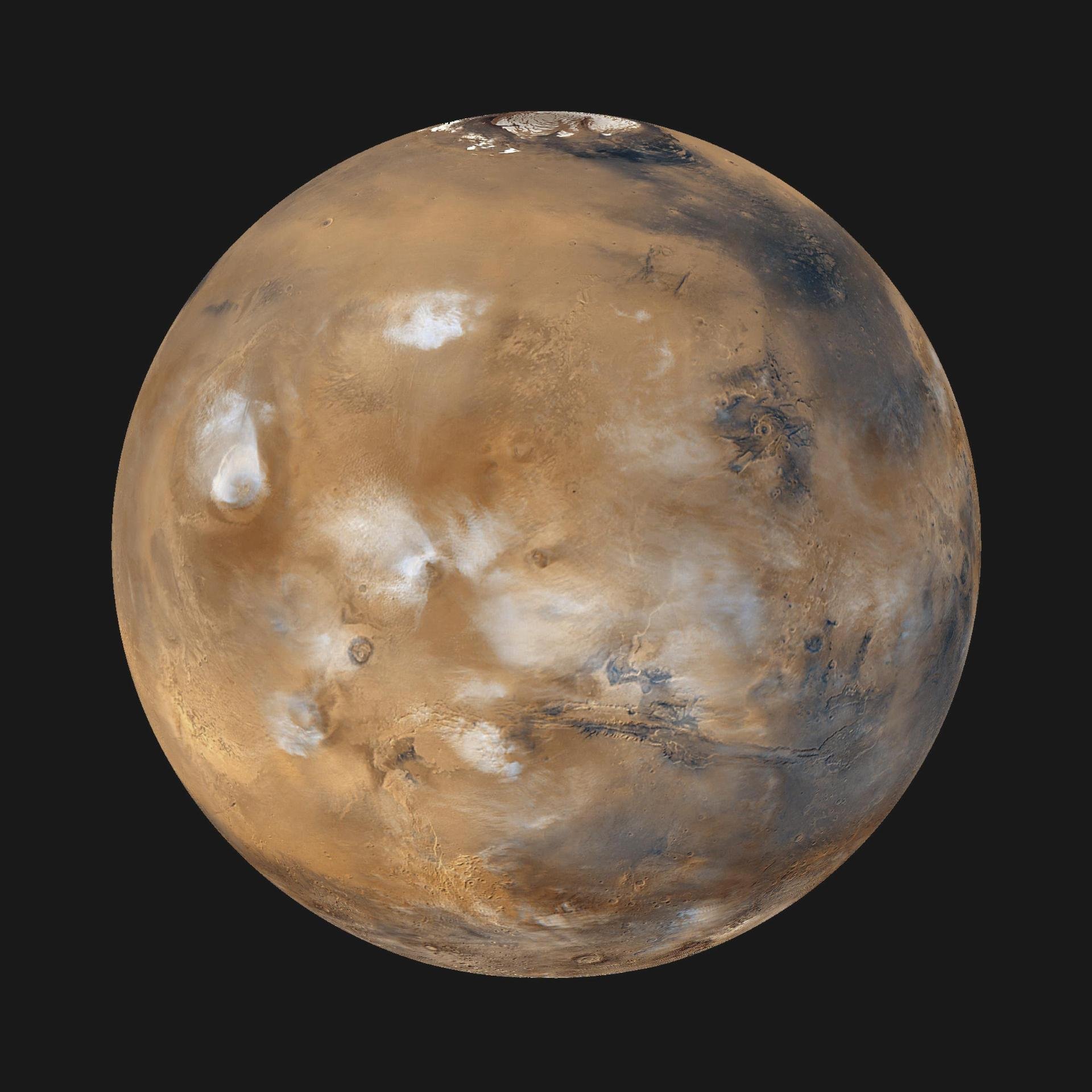

Something I love about Mars is that it's not about war, says Holst. It's about ambition and the idea of trying to find fortune by being quite aggressive. But there's the other good side to Mars, which is that because they're so impulsive and go out there on a limb, if they see someone that needs help, they won't hesitate to go and save them. So they are a hero in ways as well. And there are really beautiful things. So one of the ways that he does that is five after Figure I, you've got the trombones and the trumpets. They're separated. And so we make that really Marcato and biting with the theme as it rises. But then when the horns and tubas come in, it's legato, slurred, and it shows that they have heart and the harmony changes to A flat major, and we have the strings go into their natural part. They're no longer col legno in that colour. It just brings us a lot of warmth.

So another cool thing that I like is when the Worm [the constellation of Scorpius, that Mars rules over] comes out. Is that Figure VI? It's our second theme.

KS. Yes. And this theme appears in many different orchestrations.

GN. It does, and the way it starts, we've had the loudest crash. Colossal crashes! One of the first is a big Timpani 2 moment, and it's kind of nice to have the antiphony with the organ. It’s very low and it goes “crash!” Where could we possibly go next? Well, we go to the second theme. And you have a brightness of the snare drum. It’s like a fly that’s whizzing around your ear and then the worm comes out of the earth and that is the bassoons. All of them with the contrabassoon and the celli/bassi [in octave doubling], and you see that they have to rise up. They're writhing and trying to climb up to success and fortune, and they keep falling down. And it's that idea of it's not too loud with those instruments, even if they press and force, because of the bowing as well — they can't use that much bow — so they use a lot of weight on it and then they keep giving up. But then they strive forward, they're never going to give up. They’re Mars right? But it's the idea of a struggle, with low voices that cannot speak that loudly. If we had trombones on there, for example, or horns, it would be a lot stronger. And that buzzing fly of the bright snare drum is such an antagonistic thing, and I really make it go [vocalizes the Mars rhythm dying down then growing]. So it gives us that anxiety right there.

KS. And then it contrasts that with the entry of the oboes, English horn, bass oboe, and the violins joining in with the upper octave doublings on that theme, and then in harmony with the rest of the woodwinds and strings.

GN. Yeah, reedy. Reedy sound of the oboes. More and more voices add and we also change when the contrasting triplet figure goes to a lower part. While the worm rises and rises, by Figure VII, you have it higher with the triplet now in the lower voice in the timpani. But my favorite moment is when the snare drum crescendos to the end of its trill after Figure VII, it's like five bars, and he doesn't specify dynamics. So you have to ask yourself, what are you going to do with that? And you'll notice that there are hairpins and hairpins until that last bar before everyone goes: [vocalizes Mars rhythm]. The idea is that the snare drum can't take it anymore and snaps and everyone becomes the most espressivo and is passionate and going for it and then finally, we see Mars in its full form, and that's the entire orchestra, without contrabassoon. It's like every single other person playing the motif, and then the tune is the loudest because the entire string section now has it, and so it’s quite a visual spectacle.

KS. It really is. Yes, it sounded great today.

GN. Another moment which I think is a bit of a challenge is the fanfare. I think of it as people on horses. And maybe a chess game where the knight comes out, and they're doing their chess moves. Three measures after Figure VIII is the second time it comes, and it's not that loud. What surprised me the first time I did the piece is that the two tenor tubas need to have a lot of space. This is an example of where we need to bring the snare drum and the timpani and the strings right down. It happens at the beginning too—the snare drum is forte for some reason. You don't want to hear that; you want to hear their fanfare.

Phrasing in this is often quite difficult because it's not always obvious to the harmonic progression. To those playing the tune it may be, but if you have an accompanying line, the phrasing may not be as obvious. You have to be very sensitive to what’s happening above you.

Another moment is Figure XI with all the scurrying, scattering of all the cockroaches or something. That’s a complete anxiety and fear, which builds and builds and builds. And this is the thing, he has way too much energy, Mars. It bottles it up and it suddenly explodes, and we find ourselves in the lowest part with both the timpani and the lower strings. You know, strings in the low, low register just going for it for the last few bars where it gets longer. It can’t take it anymore like a big truck that’s in the sand and it just has to come to a crashing halt.

KS. And this kind of story, are you telling this to the musicians in rehearsal a little bit or do you assume that they know it in a way? Obviously this is a professional orchestra, and they know the piece, but if you were doing a kind of a mid-level orchestra, would you be telling this to build this character into your rehearsals?

GN. You’ve got to read the room. Especially with an orchestra at this level. Maybe with some other orchestras you need to build it up, and say rhythm, pitch, you know? But I think for this it’s great that we have so much character and things, because if something’s rushing, you can say there needs to be a calmer character or more solid pesante. You find a way to describe the sound and then they know that that means to slow down without having to say it, which is very uninspiring. When you say too loud, too soft, too slow, too fast.

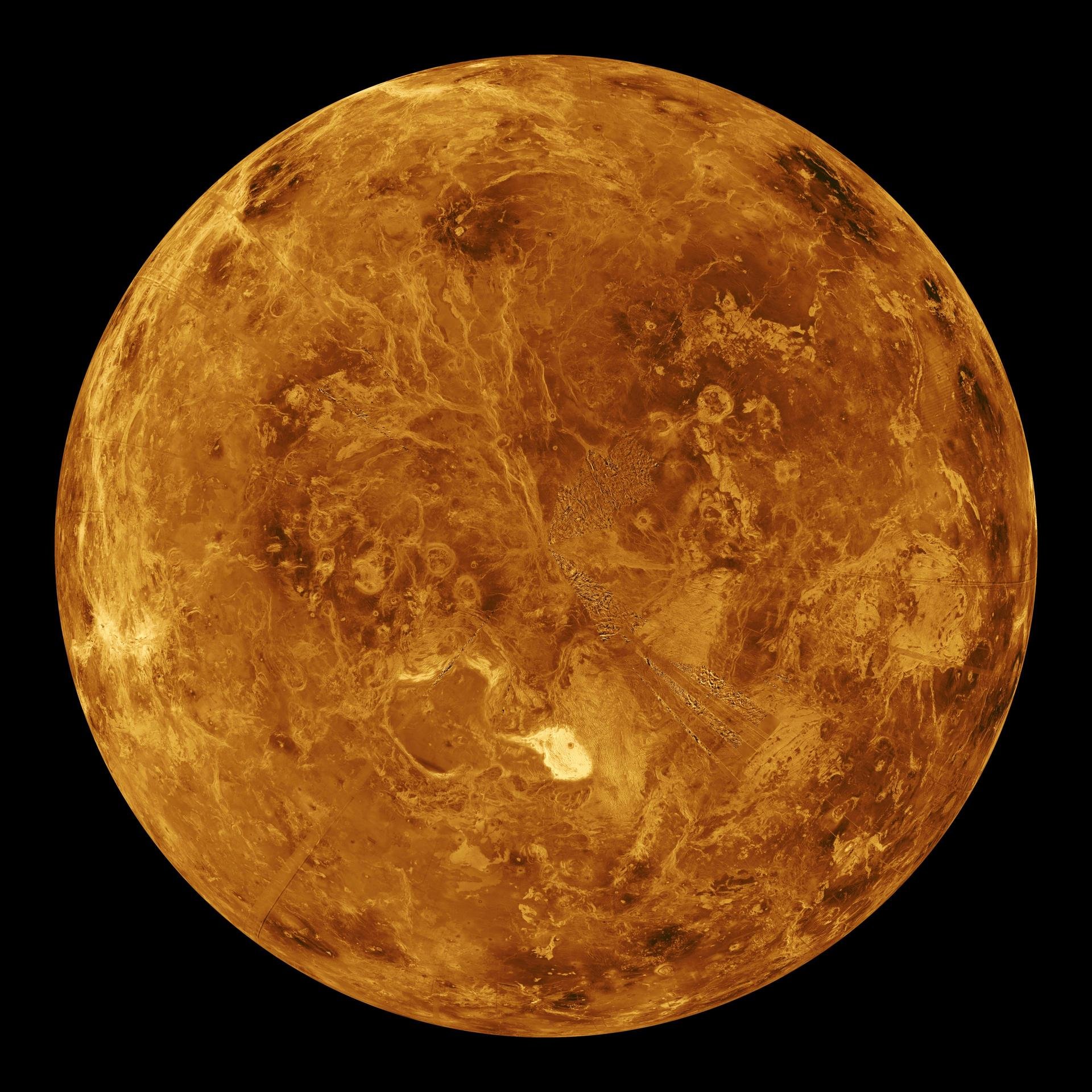

KS. Looking at Venus now, at the Andante right at the moment the violin solo comes in. These chords in the background are then passed from the oboe, English horn to the horns and then this kind of figure goes on for a while. It’s interesting here, the balance between harmony and timbre. For the oboe and English horn, you want them to create this homogeneous chord. I would assume you don’t want there to be the individual character or colour of these instruments. So my question is, how do you balance that and how do you think about these kinds of chords, when you want them to be homogeneous, when you want them to have a certain blended quality in the background?

GN. Yeah, this is a beautiful waltz, and he puts syncopations with the accompanying line to not give anxiety this time. It’s to give the sense of floating, and that we’re off the ground. But we’ve always got lots of cushions everywhere. So, right near the beginning, our cushions are the flutes and harps with horns. And he’s chosen that because I think it’s the way the horns are written, it’s a nice register. And the flutes, it’s a blended colour and then that adds to the sweep of the harps. You have to choose how fast the spread of the chords will be, but we want something very sweet and languid.

At the waltz, which you talked about, the Andante, first of all, this movement is sometimes hard to pace. We found a really natural way of flowing from one to the other, but he doesn’t put accelerando into the Andante, into the faster section, so you have to actually add that, otherwise it was very blocky.

KS. Yes. And coming out of Mars, this has to have some motion.

GN. Serenity with flow. It’s wonderful because you’ve got the beautiful horn. And when to breathe at the end of the first slur, and when to come back on is important as the conductor to give them exactly where that downbeat is, where the second beat is for the flutes to come in, for example. And then they can flow at ease, which is funny, because if you were to conduct it at ease and to be all flowy yourself, it would be a complete mess. But in the Andante, we crescendo into what is a little starburst of this bright B9 chord, and then, as you say, the solo violin is very intimate. And the solo violin then says come on everyone, and then all the violins come in and they play it. And you do have to choose a phrasing for that, and I like it to be one bar in and one bar out like breathing so that it’s a gradual in and out and it feels very natural. We’re not forcing anything, but we do have some kind of voluptuous roundness to this phrasing. Because the waltz is syncopated, but it’s still 123, 123... And sometimes just depending on how the syncopations go, I've brought out, [emphasizes the first syncopated quarter note in the oboes/horns]. We haven’t had to do that because it’s been very, very well in time this time, which is really quite nice. So if it’s going well, you don’t change it. Nice pianissimo there for the oboes.

Now you talked about the colour combination. I feel actually he’s been very smart in bringing all the oboes together—four of them with cor anglais—because they have a very similar timbre, so that helps with the blend of their colours. If you’re going to add clarinet or even bassoon, that would give it a very different combination.

KS. And having that English horn double the bottom note there balances out the overly reedy quality of the lower register to help with the balance of the chord.

GN. It might be, yeah, I think it might help if you have a third oboe. Perhaps it’s better to just have maybe two on that. Cor anglais isn’t always the strongest, but oboe 1 often comes out most strongly, so perhaps he was thinking that. I think also maybe it’s about four-part chorus, because you have the four horns which are needed because it’s a C-flat 9 chord. But then, it’s weird though, because they’re all in a very similar pitch range. It can be extremely hard to tune. Yes, very awkward.

KS. That’s the kind of timbre/harmony question where it’s supposed to sound like this homogeneous chord, but if the instruments are not balanced properly, then you’ll start to hear the individual voices too much. They want it to be this blendy horn-like thing I’m assuming, right?

GN. Yes, definitely. I guess if it was too loud, we haven’t had that problem this week, but if something’s out of tune, it’s often a balance issue. And so you say, OK, I want more of this voice or that and then it’s always fixed. It’s just amazing how it gets to that little surprise chord just by sliding down by a semitone in the third bar. Then it goes to the horns, which can actually be quite catastrophic, because they’re at the back on stage and if they enter late, it sounds like there’s a big gap right there, but we don’t have that here. It’s lovely, love it.

Going on, it’s really important to shape this because I feel that if we are phrasing together and we know where we’re going away from and we’re coming to, then the ensemble will always be perfect. We’re in line. So, if you do Figure II all mezzo forte, and you keep it sustained all the way, it would not sound like the sighing of “Elsa, Elsa...”, you know. It can also be subject to interpretation, how you phrase it, because I feel it could go many different ways. It’s one of those things that’s not like Mozart, where you can definitely hear where the height of the phrase is and how it’s brought up. Things are shifting bar by bar, but they’re not necessarily more energetic than the other, and sometimes you could bring them down to make it special. Or you could emphasize it.

So we’ve chosen at Figure II to go "TEE-dum, TEE-dum," And then because we've heard it twice, and because the third bar has just one quarter note on that top note, now we have that softer [sings melody, starting quietly and grows] and then we keep going [continues singing]. And I chose that longer phrase. You could go [sings melody, loud then soft then loud] to go to there, but I thought that would break up the phrase way too much.

There is a lovely line with the cor anglais and viola there, a nice bass line at the Animato. You look at how the harmony goes down and down and down in pitch, but it has a crescendo and the crescendo is really forced. We took it out because it makes it much more relaxed. And then, by the fourth bar of the Animato, we change and we add energy. That makes it much more natural for a crescendo into the pizzicato, which needs to be fully supported. There are two bars of crescendo and also a bit of a ritenuto already in those three measures before Figure III. But it's very intimate; there are many beautiful solos. Six measures before Figure IV, he’s overscored the strings. I would probably halve the section for that because you've got solo oboe, solo clarinet, and they're so sweet and soft, and yet there are many accompanying voices there.

Jade Roth [JR]. So how do you compensate for that there? Do you just tell all the violinists to keep quiet there? Or did you actually halve the sections?

I didn't halve the sections, but I might do that next time because it's always been a problem. We make it pianissimo. We change where we phrase to. A lot of people crescendo in the strings to the note change that they have, but actually the oboe is diminuendo-ing at the end of their phrase. So, I put a crescendo to the second beat of the Largo bar and then come back because it's [sings]. That would go with the other line, but it was still too loud. So, we just brought everything down.

And then you see over the page, which is not great for a conductor, that Figure IV is a Largo. So we really need to relax as the cellos come up, and often they think “ohh, I'm coming up, so I soar and I become the Elgar cello concerto.” And we have, say, it's like bubbles: they lighten up to the top. Yeah, also that viola line. We started on an upbow at the beginning of the week, but I said no, again, it's: “Gilda, Gilda” you know, it is a sigh, right there. Beautiful cello lines; really touching. So sweet, this movement.

KS. It is, yes.

GN. You might look at three after Figure V. You have the violin split in thirds, so hard to feel very comfortable about it; when they felt comfortable about it, they played it very loudly. It's a lovely colour there, because the horn has that call [just before] and now you've got the flute with the line.

Lovely organ-like combination at four bars before Figure VI. You've already got it a little bit at six bars before Figure VI with the horn and the bassoons very close together in pitch. But then, the bass clarinet and contrabassoon at three bars before Figure VI—that is just like adding the pedal of the organ. It’s very easy for that to all start late in the lower registers. But you know what? It's kind of exactly like an organist in an English church. They would make it speak later anyway.

KS: Yes, it's a morendo though, right?

I don't mind if it's a little bit intimate there. It's personal. But of course, the cello has the accents and wants to be on the top of the phrase, so they're often right there on the beat. And then we hear it later. So it’s always a bit of a battle.

[There] is a very cool moment at two bars before Figure VII. And it's very hard to hear the way it's written. So if I were to make a set of parts, I would bring down everyone else in the orchestra, and then for the horns, the triplet line is what we really want to hear [singing the horn line]. All of the triplets, it’s very special there.

And then we had a nice celesta solo at the end.

KS. Is the organist up in the organ loft tonight or is he staying on stage? [he wasn’t on stage in the dress rehearsal]

GN. He's staying on stage. And we've got a little sneak trick for the choir. He's going backstage for the chorus to play the harmonies. It’s such a common thing with this piece that the chorus is backstage and what they hear—and also, probably not be able to hear it very much to all, quite frankly—it's true they get flatter and flatter in pitch, and so it's very natural, and it happens. So there's a lot of tricks of the trade and I've even had everyone with headphones, and it being played right in the ear. And that was amazing! But this was very good. Our intonation was very good this morning, and we had Jean-Willy playing.

KS. Is he playing piano?

GN. Well, it was electric.

KS. Electric keyboard, so he's able to soften it?

GN. Yes, exactly. We can't hear it on stage.

KS. That was a beautiful effect [the choir] being off stage like that, the way it's like a band-pass filter. As if you're just hearing this, not the highs, not the lows. And it's very distant.

JR. It’s very eerie.

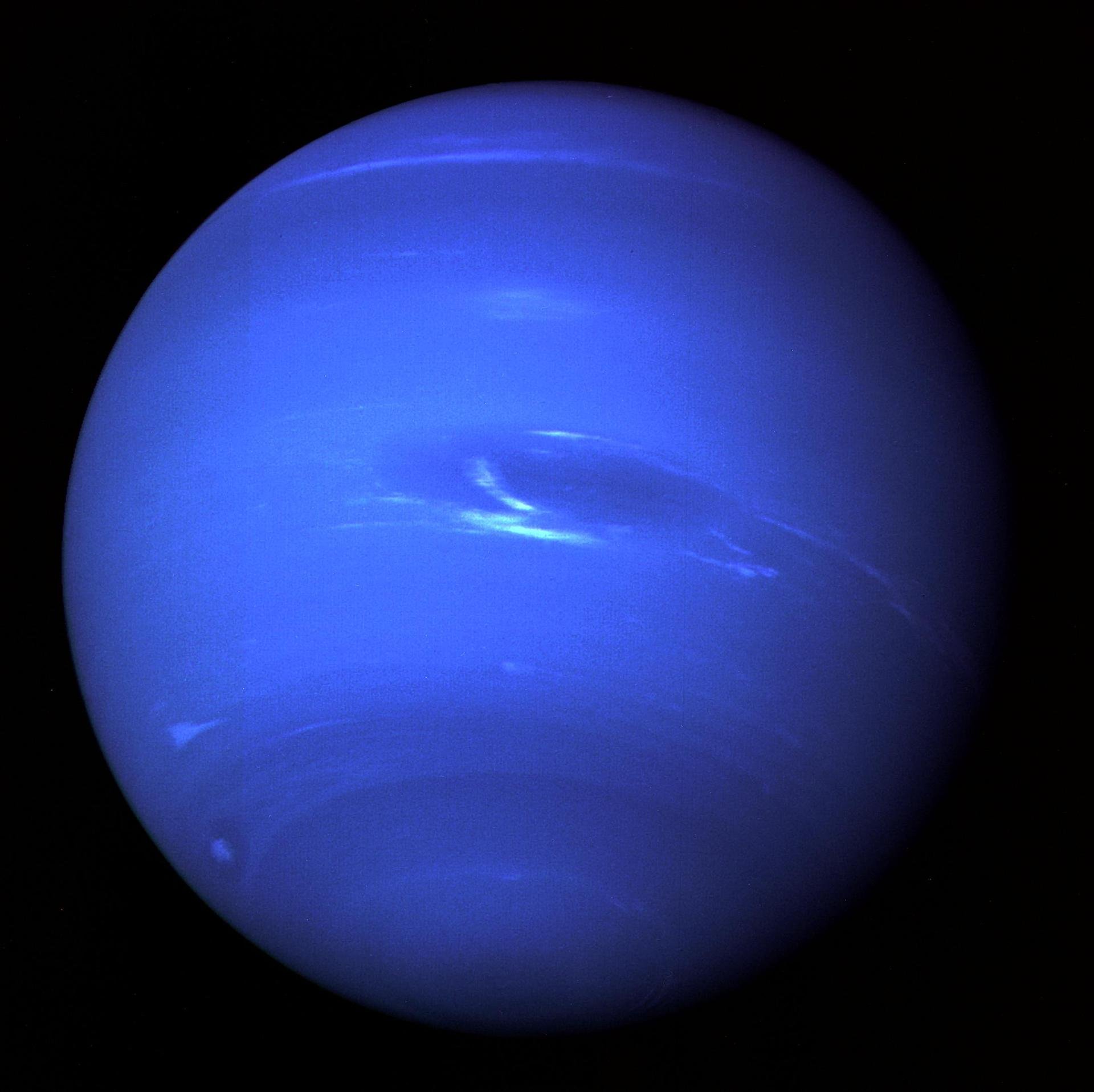

GN. Saturn is Holst’s favorite.

JR. One thing we talked about at the break was the combination of the harp harmonics with the flutes, and how that fuses together.

GN. Definitely, yes.

KS. It creates a really unique blend with the attack of the harps, but then the sustain of the winds.

GN. Yes, and you have to choose, because ensemble here is incredibly difficult for the flutes, and when to breathe.

KS. OK. Yes, because it's not at all clear.

GN. I said to them that the flutes lead, because otherwise they end up hearing the harp sound and starting as a kind of a blend or an echo out of the harp, but then you get things very out of time. And the idea is that it is so together, exactly like a clock of life, that it feels like timelessness. So I feel at the beginning of this movement a lot of people are “Wow, it's so slow. There's nothing going on. Why are we here?” And then you had this long double bass solo that we've made rather sinewy so that it sounds like a curmudgeon, muscles aching, and like an old person, like walking along.

At the end of the double bass phrase, there is a question of whether you want to have a crescendo into where the upper strings enter. And I added one again for the bass oboe, a crescendo 4 bars before Figure I, and it just adds a little bit of [growls], angry and aching and a bit of curmudgeon just to have that last word and the last eighth note sounds [sings] very tired and fed up with life. We think of it as very low because the melody’s in the bass, but then it has very high moments too, like the oboe 1 and the cellos are so high as well for their register. And then the bass oboe is really low, so I feel like it's showing both the old person’s grumbly nature, but also how weak they are. This is Holst saying someone on their road to death through life. It turns a switch at Figure I. Tempo-wise, we go a little bit faster. We have a new bass line that is now four notes coming down rather than the two oscillated harmonies.

And we have this Brahms-like chorale in the trombones. And we say, “What is this? Is this beautiful nature? Is this living life and contemplating?” And suddenly we realize, really when the strings start nine bars before Figure II, that it's a pomp and circumstance march and it's one of the slow ones. It's very elegant and regal, and it's like you've got that procession up in Saint Paul's Cathedral when you're coming closer and closer to the altar.

Then you come back to the plodding character, and the flutes give a soliloquy about how cold and harsh life is. And we say, in this arid earth do we want to live at all? You know it's quite dark and horrifying, but as it grows, we've finally realized where we're meant to go, and it is our time to transfiguration to go into the afterlife. And the bells strike and that's the moment where it snaps, and our soul is taken, and we die. And I feel all that beforehand: it's life and it's accepting life, it's finding some beautiful parts of Brahms-like chorale, it's finding their elegant procession of life—the good and the bad. This moment of snap! Oh my God! Clatter, clang. It's so intense on stage for that because you have half the orchestra on the beat, half of them off the beat, and you have to keep that while the low melody happens. That cannot go out of time, otherwise it's a mess.

KS. Is that at the Animato?

GN. At Figure IV. Yes, as it goes on and on and on. We have a few moments of maybe the heart’s starting to go and become irregular. And then at Figure IV, it's the moment and suddenly, when we find Figure V, our soul has left the body and we're floating, and we've found our own new path. And he was really into Hinduism at this time. So he probably believed that the soul went off to something else. And you hear the double bass line again, but now it's so sweet and smooth and flowing, and it no longer has those muscly aches. It's beautiful. It's the most beautiful thing.

JR. If I can bring out a specific spot, it's interesting hearing these programmatic elements just after Rehearsal II. There's a really interesting chord in the third measure after Rehearsal II, where it's very deep and full. But then as it decays, it has a really interesting quality.

GN. Yes, you can choose how you do this one. I chose something sharp because I thought it was anguish rather than ache. Right. This is now more of the flash of realization that death or doom is coming. So I asked them to have a forte with an accent, a sharp accent, and then third and fourth beats to come away there. So it's really planned. It's a hard one because you've been plodding like a big horse, you know. And then suddenly, [imitates loud crash]. It’s exciting. And then you choose. The flutes have tenutos and in this piece, tenutos mean a push. And it's like an accent, but it's a dull thud push, or a pull really.

KS. Do you notice that Holst is skilled with writing for wind orchestra in this symphonic work? As a conductor, do you really notice it?

GN. Yes, it's also just a massive play for the woodwinds.

KS. It is. He's engaging them more.

GN. All the time. It's funny, when you said doublings, I was like, what do you mean, quadrupling? Because they’re always playing as a whole section.

KS. Yes, I call it couplings. You're coupling registers, coupling different pitches or coupling all the different instruments so that you don't get the confusion of the doublings, tripling, quadrupling, 9-tuplings.

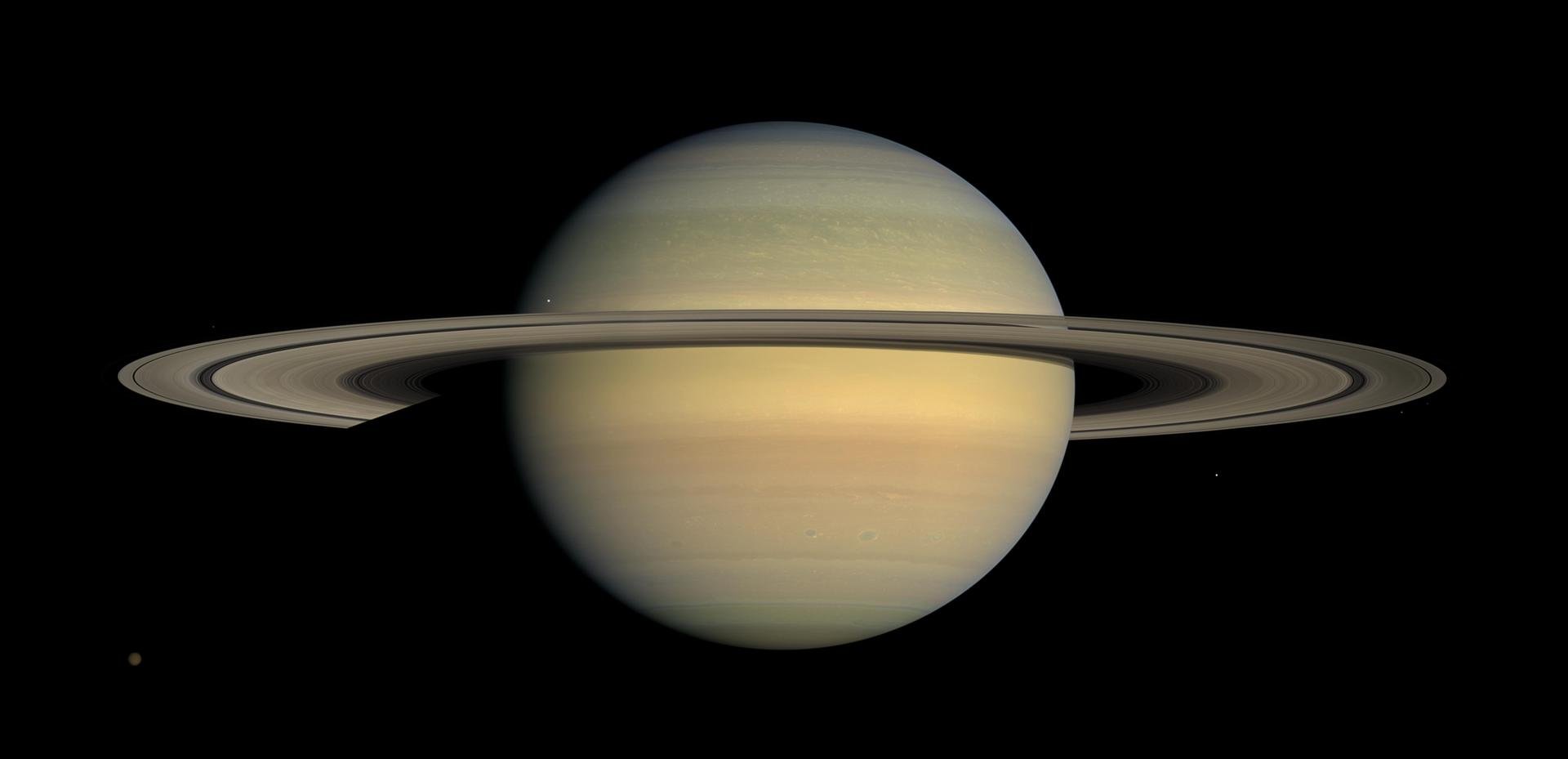

GN. Already in the first four bars of Uranus you have fermatas, and you know you have the brass in unison, octaves really. And it's like, “Here I am! I'm the magician! The crazy professor.” And I think of each group of four notes as him posing in a different way. So, every four-note group is a different personality.

And then the bassoons. It's very important for them. I really want them to go [sings accent on beat 4], because everything's on the edge. And this one, he's out of control again, but in a funny way. It's not like the seriousness of Mars. And all his experiments are catching on fire and he's a mischievous little gnome.

It's like the Ducas Sorcerer's Apprentice and you’ve got the xylophone bringing that kind of skeleton, Halloween feel. A lot of these lines in the upper strings, the first violins are so high at nine bars after Figure II. And most people will go [sings lyrically]. But I think that's really out of character because you've had the impish pizzicato with the little mischievous winds and then [sings with strong downbeat emphasis].

So he's on the tightrope, and he's almost falling off all the time. And then before Figure III, they go “Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha.” So we have to actually choose a lot of phrasing that's not really in the part otherwise it doesn't come out like that. And then the other thing is when you look at after Figure V, the timpani are having their heyday. They do get to do the tune of Jupiter. That's also very cool. But this is a real fun one for all the timpani and percussion. And I feel like he's walking down the street. He's all suave and thinks he's really cool, and then he falls over and it's always the percussion that show that, tripping over with the shoelaces or something like that. So it's a 3/4 bar whenever that comes in. You see the timpani have a big solo right there, and that's a lot of the fun of this movement: the timpani always have that last trip-up of the phrase. And the mighty power of him at Figure IX. That chord is amazing. Low organ pedal E.

JR. Is that the one that you feel?

KS. Yes. That's so deep there.

GN. Yes. So it takes time for the downbeat to really set that tonic chord. And then the dissonance of the polyphonic chord and how it's so much energy that it has to play out with the storm going away. The thunder and lightning just gets further and further and softer and softer until we have our Don Juan moment where he completely expires.

KS. Yes, such a good contrast between Figures VIII and IX, right? Like the difference in balance there is remarkable.

GN. Well, look at one bar before Figure VIII. Tada! Then the midnight bells of the harp. It's like Big Ben chiming. And we have our sweet sojourn with the strings. Very romantic. After Figure VIII, the 6th bar. Yeah, it's very cool.

GN. So movement three is actually one of my favorites because he changes colour every single beat, and everyone just has [sings eighth-note fragments]. And then there's the 2 over 3 as well rhythmically, so it's always on its feet. You have to know when it's winding down or when it's suddenly getting louder. It's very important to have those contrasts.

And then the third theme at Figure III, this is the idea, he says in the book, when everything that Mercury touches, they absorb and so it's always an accumulation. And so we start, it’s very legato and it rolls into the third bar of every three, but sometimes it rolls into the second bar of every three because of the harmony change. And that keeps us always like shifting sands of the desert. It's always moving around. And you really have to bring out that shape to make it have that winged messenger feel.

JR. Especially when they're switching so rapidly between different instruments. Are there any particular techniques to help it feel like one gesture rather than fragments?

GN. Well, fortunately, it's not for the large orchestra. The 2nd and 3rd movements have smaller sections. There are four horns for this and two trumpets, so it's like a chamber orchestra. But of course, a lot of winds. And so the winds are very involved. The Trumpets hardly play at all, actually, in this movement. It's very sparing with the timpani. But you are passing on very rapidly from one instrument to the next. But they're often sitting next to each other. So that's why it works so naturally. And usually it's very, very easy. The only thing is when it gets into hemiola rhythms, and he adds accents for it. But because it's running so quickly, it can sometimes feel like it's rushing a little bit, so we have to be very tempo giusto. Because people are next to each other, it makes it a lot easier. And this hall is so beautiful to hear each other in.

KS. It's really great.

GN. That timpani roll, you can hear it so nicely and this hall, it's fantastic and he's doing great job, of course.

GN. And then Jupiter, on the other hand, it's massive and everyone's back. Yes, very standard. It starts with horns and violas and celli. Tchaikovsky always used that combination.

KS. True. And Holst is balancing the contrast between this smaller combination playing the theme versus when everyone plays in unison.

GN. Exactly. And even the timpani have the tune. I think that's one of the reasons why he has two timpani because then he can make melody, make them sing. Very cool glockenspiel lines as well, both in Mercury and this one. Nice tambourine rip.

KS. Yes, that's true.

GN. That needs to be added to the part, it's not necessarily obvious in the part. The horns have a lot to play in this one and I wonder, this is probably overthinking it a lot, but Siegfried has no fear, and so he always has a very positive disposition and Jupiter also is full of jolliness. It's not joy. It's not exalted, ecstatic; it's very content. We have to be careful about the tempo, making sure that everything can be heard in the space, and also that we are walking down the road rather than running. And I feel like there's a bit of drunkenness and some popular songs in here, so it could be like you're walking out of the bar, like Falstaff. Then you have the English tradition, the great choral writing. He wrote for and had a women’s chorus. But he would have been versed in the boys’ choir and just the idea of England, really loving that, “Vow to thee, my country.” I sang this song when I was a little girl at school, so I know the words and we really follow the text. I really love the song. It's just so beautiful. Right at the end when you hold on the B-flat chord and then the violins enter. It's like a Disney moment. It feels very cheesy, but it's very good. It's very hard to pace this movement.

KS. Do you feel that’s because much of the orchestra weren't playing before, that they come in and they're not ready to go?

GN. No, it does start with the second violins and then having to start and [sings violin part 16th notes]. We've already got a cross rhythm at the very top. So it is hard to set that, but they're very strong. It's more that Holst has them play pesante [sings strings melody]. And then it goes faster again and it has [imitates 16th note passage]. Sometimes it's accelerando and then you start really slow again and have a little bit of a polka and it's got a lot of accelerandos. Just knowing the best way to pace it, I feel, it’s different every time and you have to find it because it's not written.

KS. It depends on the hall too and the and the orchestra, right?

GN. Yes, definitely. But, you find the most supportive and strong way for the week. And then it's really great and I think we found it this week, so I'm very happy about it. All right. Thank you.

KS. Yes. Thank you. We appreciate your time with us today.

Recording

Holst, G. (1987). The planets: Op. 32 [Album recorded by Orchestre symphonique de Montréal & Charles Dutoit]. Decca. (Originally work published in 1917)

Images

Source: https://science.nasa.gov/